By John D. Stoll

Oakland University didn't top Matthew Henry's list when he

started hunting for colleges in Michigan to attend. But one visit

to the spacious campus, situated on a serene 1,400-acre estate

donated by the heiress to the Dodge auto-making fortune, sold him

on the school.

Four years after making that decision, the 21-year-old senior is

capping an education made possible, in significant part, by a

corporate behemoth from another part of the world. German

industrial giant Siemens AG provided software, instruction,

curriculum, technical support and sophisticated gadgetry to make

Mr. Henry and his fellow Industrial and Systems Engineering

classmates fluent in some of the most used tools in the profession

they aim to pursue.

"Siemens has no doubt played a bigger role than I gave much

thought to before starting," Mr. Henry says. He came to find out

that his chosen focus would require learning what is equivalent to

a software language. Siemens' "Tecnomatix" digital manufacturing

programs are a fixture in Oakland's department.

Robert Van Til, director of Oakland's Industrial and Systems

Engineering program, says experiences like Mr. Henry's are a

meaningful template for future students of design, engineering and

other sciences. While companies have long provided grants, engaged

in joint research, funded scholarships, and offered internships or

apprenticeships, an era of close-knit working relationships between

companies and undergraduates in classrooms at four-year

universities is now getting under way.

Tim Sands, the president of Virginia Tech, says that student

experience with real-world corporate problems will become table

stakes in the job market in years to come. Students "really need to

be embedded within an employer that has real-life problems, and to

look at how they solve those problems," he says.

Mr. Sands has welcomed several corporate partners to Virginia

Tech's campus in Blacksburg, including Qualcomm Inc., Caterpillar

Inc. and General Electric Co. New initiatives require students to

spend extensive time working on the actual riddles companies are

trying to solve to get a degree.

Partnerships like this remain somewhat rare, Mr. Van Til says,

but they are a hot subject at education conferences. "There's a

real push to get academic programs to actually take the tools like

these and integrate them."

Elizabeth Popp Berman, a University of Michigan professor of

organizational studies and author of "Creating the Market

University," says there have long been critics of corporate

meddling in four-year universities. Often, funding from companies

for research or other academic pursuits comes with strings

attached, she says.

Corporate involvement in curriculum may also narrow the skills

that students pursue, ignoring information or career pathways that

may not apply to a company's business.

But colleges are more open to corporate partnerships as budgets

are squeezed and student debt loads rise, Ms. Berman says. "The

tighter the budget the institution has, the more open they are

going to be," she says. "It's hard to reject this support outright

because of the position the students are in." Companies also offer

deep-pocketed support for a "practical applied model" that doesn't

break the bank, she says.

The Siemens partnership, partially funded by the company, has

been on Oakland's campus for a decade and serves hundreds of

students. They have used the partnership to complete projects at

hospitals, banks and aerospace companies. To set up a facility like

the Siemens lab where Mr. Henry studies would cost a university

hundreds of thousands of dollars, not including steep licensing

fees for software and tech support.

"We're not asking them to create a factory or our employees for

the future," says Barbara Humpton, the CEO of Siemens' U.S.

operations. Siemens isn't necessarily hiring all the students who

use its tools in class, she says, but it expects those students

could work for Siemens customers or suppliers.

Caterpillar, International Business Machines Corp. and

Amazon.com Inc. have implemented similar efforts. A company's

branding on curriculum and classroom instruction is often

unmistakable.

Students at Cal Poly University's Digital Transformation Hub

walk through a door proclaiming the department is "powered by AWS,"

short for the Amazon Web Services cloud-computing product. Here,

students participate in the AWS Cloud Innovation Center, about a

dozen of which are embedded at schools around the country.

Instead of being a classic sponsorship, like an advertising deal

at the university's football stadium, programs like the Cloud

Innovation Center are staffed by Amazon employees, bringing Amazon

business principles into formal education. In this case, students

interested in solving public-sector problems learn how to think

like an Amazon employee; the company's leadership principles, such

as "customer obsession," are taught in college workshops.

Paul Jurasin, director of the Hub, says the partnership is

designed "to provide our students with learn-by-doing activities."

Amazon funds the operation but knows that most who go through it

will use Amazon Web Services as clients or in outside organizations

instead of as Amazon employees, a spokeswoman says.

Corporate America suffers less from a skills gap, and more from

a "failure to develop its discovery muscles," says Dave Calhoun,

chief executive of Boeing Co. Before he was CEO, he personally gave

$20 million to Virginia Tech in 2018 to create a "Discovery

Program" to bridge a "multidisciplinary gap" that many students

suffer from when leaving college. "You're now trying to solve for

things outside just the raw technology, and we have very few people

who are really skilled at doing that kind of thing," he says.

"Usually they are in their mid 40s or early 50s."

A task force assembled by the American Association of State

Colleges and Universities found in 2017 that such relationships are

becoming more attractive as institutions look "to attract the

resources, relationships and recognition necessary for these

institutions to be competitive in an environment marked by

declining state funding and continued questions on the value

proposition of public higher education."

George Mason University's new president, Gregory Washington,

says educators aren't necessarily inclined to go out and find

corporate allies. His charge to faculty is to "partner or perish,"

playing off the old "publish or perish" adage that long measured a

professor's success. Mr. Washington, an engineer by training, says

research is important, but it can fall short if companies don't

have a seat at the table.

There is urgency driving Mr. Washington's rewiring of George

Mason's philosophy. Amazon is aiming to add tens of thousands of

jobs at a second headquarters in Arlington, Va., located about 18

miles from Mr. Washington's offices. While George Mason is held up

as one of the state's deepest pools of technical talent, its

president worries that Amazon will take its programs (and jobs)

elsewhere if unwelcome on his campus.

Amazon currently has several initiatives with George Mason.

Amazon officials pointed to George Mason's commitment to invest

$250 million at the Arlington Campus, which is close to Amazon's

second headquarters, adding 1,000 new faculty and doubling the

number of computing majors in the next five years as evidence that

the university's commitment is deep.

"Universities tend to be more insular entities -- they focus on

graduating their students; they focus on taking care of their

faculty," Mr. Washington says. "Now? We can't meet the mission of

our future, we can't tackle the big challenges that the country

needs us to tackle without real partners."

Mr. Stoll is the business columnist for the Journal, and a

graduate of Oakland University.

Write to John D. Stoll at john.stoll@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 09, 2020 12:16 ET (17:16 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

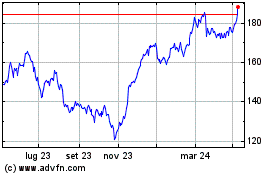

Grafico Azioni Siemens (TG:SIE)

Storico

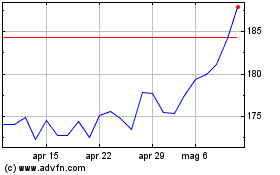

Da Mar 2024 a Apr 2024

Grafico Azioni Siemens (TG:SIE)

Storico

Da Apr 2023 a Apr 2024