By Jimmy Vielkind, Laura Stevens and Katie Honan

Jeff Bezos and other top Amazon executives gathered in Seattle

on Wednesday to decide whether to go ahead with its planned

headquarters in New York City.

Brian Huseman, vice president for public policy, was on the

phone, and the news was not good.

He had met with Andrea Stewart-Cousins, the majority leader in

the restive New York Senate, and separately with three union

leaders in the office of Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a champion of the

project who brokered a discussion to allay labor's concerns.

Nothing in Mr. Huseman's call allayed growing fears at the

company that the fiercer-than-expected backlash against the $2.5

billion development in Long Island City, Queens, was generating

negative publicity and political uncertainty.

Mr. Bezos had signed off on the previous decisions in Amazon.com

Inc.'s lengthy public contest to locate its so-called HQ2, and on

Wednesday he and his team decided it was time to pull the plug,

according to people familiar with the matter. It was worth the

embarrassment and negative publicity in the short term, they

reasoned, to avoid a yearslong problem in New York.

Amazon made the news of the pullout public on Thursday, leaving

Mr. Cuomo and the deal's other biggest supporter, New York City

Mayor Bill de Blasio, stunned and chagrined. The final decision

followed dozens of meetings with New York lawmakers and

communities. Even after months of talking, Amazon's team and vocal

New York critics failed to allay the other side's concerns,

convincing company executives that compromises would be too hard to

achieve.

After a yearlong nationwide search for a site of a second

headquarters, Amazon announced in November that New York City and

Northern Virginia were the winners, splitting the prize with each

location promised at least 25,000 new jobs.

In return for Amazon's job creation and investment in New York,

city and state officials agreed to provide up to $3 billion in tax

incentives. Mr. Cuomo had warned executives that the deal might

spark a minor backlash, but that it would go through.

After the announcement, a group of state and local leaders

seized on the incentive package and questioned why one of the

richest companies in the world was getting subsidies at all. Cries

of corporate welfare and vulture capitalism became refrains among

progressive Democrats, including the state's newest political star,

U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, as well as from within the

newly Democratic state senate.

Those politicians, together with union leaders, also beat a drum

about Amazon's stance against organized labor. Members of the New

York City Council joined in, grilling company executives at

hearings in December and January over their record with unions and

about the closed-door negotiations with state and city officials

that had produced the biggest project-based incentive package in

state history.

"This was a secretive process intentionally structured to avoid

a substantive public review in advance of any commitments being

made," City Council Speaker Corey Johnson said at a Jan. 30

hearing.

Amazon executives were completely unprepared for the backlash,

according to the people familiar with the matter. Polls showed a

majority of New Yorkers supported the new campus, but Amazon grew

more wary when state Sen. Mike Gianaris, who represents the project

site in Queens, was nominated on Feb. 4 to the Public Authorities

Board. The seat meant Mr. Gianaris, an outspoken critic of the

deal, could potentially veto the proposed campus.

A day later, his leader, Ms. Stewart-Cousins, met with several

Amazon lobbyists in her office at the State Capitol. It was a

cordial exchange that lasted 20 minutes, according to people

briefed on the meeting.

By Friday, Feb. 8, the first indications that the Amazon deal

was fraying surfaced with reports that company executives were

reconsidering the New York campus.

Ms. Stewart-Cousins, a Democrat from Yonkers, said Mr. Huseman

-- who was not in the earlier Capitol meeting with her -- called

her on Feb. 8 and Feb. 9. They spoke generally about the project,

and Mr. Huseman asked about Mr. Gianaris's nomination.

She said she told Mr. Huseman that Mr. Gianaris's perspective

was important because he represented the area where Amazon had

proposed to locate. She also said she conveyed to Mr. Huseman that

she would work with Amazon but that she had criticisms about the

way the deal was being processed.

"Because there has been no real legislative input, it was

important that I at least give an opportunity to a person who's in

the district," Ms. Stewart-Cousins said, referring to Sen.

Gianaris. "There would certainly be questions asked. But that's it:

he wasn't representing himself, he's representing us."

Ms. Stewart-Cousins said Mr. Huseman didn't have any specific

reaction.

Days later, Mr. Cuomo called Mr. Huseman as well as several

other Amazon executives to meet Wednesday morning with leaders of

the state's AFL-CIO, Teamsters and Retail, Wholesale and Department

Store Union.

Unionizing Amazon's workers had become a bigger issue. Mr. de

Blasio had come out strongly in support of allowing unionization,

despite Amazon saying it wouldn't budge on the issue. While

Amazon's official position is that it respects employees' rights to

unionize, Mr. Huseman had been grilled at a three-hour City Council

hearing at the end of January on the issue. He said the company

wouldn't remain neutral if workers attempted to organize.

In a conference room near his 39th floor office, Mr. Cuomo

opened a discussion about fair practices for workers organizing at

Amazon's warehouse on Staten Island, people familiar with the

meeting said. The union leaders asked about rights of access for

organizers and a commitment that Amazon wouldn't treat them with

hostility or retaliate against workers who spoke to them.

After an hour, the meeting broke with cordial handshakes. RWDSU

President Stuart Appelbaum said he planned to draft a written

framework.

"We left there with the understanding we were going to continue

conversations. It was a good meeting," he said.

Mr. Huseman's report to Amazon's top brass Wednesday didn't

bring any comfort.

Company officials are sensitive to being wanted, some of the

people familiar with the matter said. They developed their HQ2

campaign in part to draw attention to its ability to create jobs

and investments -- points they had stumbled at making previously,

in part due to Amazon's slow, steady build-out across the

nation.

At first the executives thought they could stick it out and

probably win the battle, but the meetings with the union and Ms.

Stewart-Cousins served to push Amazon out of the deal.

Now the 25,000 jobs destined for Long Island City will be spread

out among the company's nearly 20 corporate offices and tech hubs.

The company has already initiated expansion plans in many of those

places. New York will continue to grow too, according to some of

the people. The company had already planned to add jobs slowly and

had plenty of space in its existing office space in the city.

Still, the decision stung.

Amazon spokesman Jay Carney, a former White House press

secretary, called both Messrs. de Blasio and Cuomo on Thursday

morning with the bad news -- just minutes after their top aides

attended a community meeting in Queens about the Amazon

project.

"There wasn't a shred of dialogue. Out of nowhere they just took

their ball and went home," Mr. de Blasio said Thursday evening at

Harvard University.

Write to Jimmy Vielkind at Jimmy.Vielkind@wsj.com, Laura Stevens

at laura.stevens@wsj.com and Katie Honan at Katie.Honan@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 15, 2019 19:37 ET (00:37 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

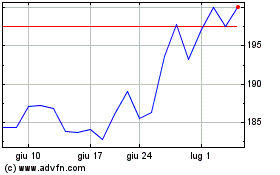

Grafico Azioni Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Storico

Da Mar 2024 a Apr 2024

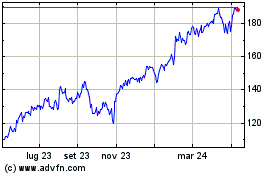

Grafico Azioni Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Storico

Da Apr 2023 a Apr 2024