By Christopher M. Matthews, Bradley Olson and Allison Prang

Some of the banks that helped fuel the fracking boom are

beginning to question the industry's fundamentals, as many shale

wells produce less than companies forecast.

Banks have begun to tighten requirements on revolving lines of

credit, an essential lifeline for smaller companies, as these

institutions revise estimates on the value of some shale reserves

held as collateral for loans to producers, according to people

familiar with the matter.

Some large financial institutions, including Capital One

Financial Corp. and JPMorgan Chase & Co., are likely to

decrease the size of current and future loans to shale companies

linked to reserves as a result of their semiannual reviews of the

loans, the people say. The banks are concerned that if some

companies go bankrupt, their assets won't cover the loans, the

people say.

JPMorgan Chase declined to comment. Capital One didn't respond

to requests for comment.

The tightening financial pressure on shale producers is one of

the reasons many are facing a reckoning going into next year.

Chevron Corp. said Dec. 10 that it plans to take a charge of $10

billion to $11 billion, roughly half of it tied to shale gas

assets, which it said won't be profitable soon. Other companies are

expected to follow suit in writing down assets, according to

analysts and industry executives.

The heat is greatest for small and midsize shale producers,

including many whose wells aren't producing as much oil and gas as

they had projected to lenders and investors. Some of those

companies may be forced out of business, said Clark Sackschewsky,

the managing principal of accounting firm BDO's Houston tax

practice. Large companies are likely to weather the blow because of

their size and global asset diversity, but for some smaller shale

operators, tightening access to bank loans could prove

disastrous.

"We've got another year under our belts with the onshore

fracking assets, which includes less than optimistic reserves

results, less production than anticipated, a reduction in capital

investment into the market," Mr. Sackschewsky said.

Oil and gas producers expect banks to cut their revolving lines

of credit by 10% as a result of the reviews, according to a survey

of companies by the law firm Haynes & Boone LLP. The cuts may

be more severe, say some people familiar with the reviews.

Banks have extended billions of dollars of reserve-backed loans,

though the exact size of the market isn't known. JPMorgan said in a

regulatory filing in September that it has exposure to $44 billion

in oil and gas loans, and Capital One said in October it has

extended more than $3 billion in oil and gas loans. It wasn't clear

for either bank what proportion of those are backed by

reserves.

Banks have typically applied a 10% discount to the value of

reserves, meaning a shale company could borrow against 90% of its

reserves as collateral. But some are now discounting the value by

as much as 20%, the people say.

Meanwhile, some regional banks have begun writing off bad energy

loans. Net charge-offs shot up at Huntington Bancshares in the last

quarter. The Ohio-based lender attributed the move primarily to two

energy loans where the borrowers' production had not met

expectations, Huntington Chief Executive Officer Stephen Steinour

said in an interview.

"Geology and the assumptions were just flawed," Mr. Steinour

said.

Many investors have lost faith in the viability of shale

drillers, as natural-gas prices stayed low and many companies broke

promises on how much their wells would produce and when they would

begin to turn a profit.

As investors have retreated, cracks have begun to show. Energy

companies accounted for more than 90% of defaults on corporate debt

in the third quarter, according to Moody's Investors Service. There

were more than 30 oil-company bankruptcies in 2019, exceeding the

number in 2018 and 2017. Exploration and production companies are

now carrying more than $100 billion in debt, according to Haynes

& Boone.

Skepticism among banks has grown in part because lenders have

more closely scrutinized public well data on production and seen

that it is falling short of forecasts, as a Wall Street Journal

analysis showed earlier this year.

Specifically, banks have begun questioning shale producers'

predictions about their wells' initial rate of decline, which are

proving overly optimistic, according to engineers. If shale wells,

which produce rapidly early and then taper off, are declining

faster than predicted, questions arise regarding how much they will

ultimately produce.

Some lenders have flagged publicly that they will be less

generous with loans in the future. "With respect to any new energy

loans, we are highly cautious; it's a very high bar we must clear,"

said Paul B. Murphy, CEO of Cadence Bank, in an October call with

analysts. The firm operates in Texas and the southeastern U.S.

Bank lending has slowed across the board in the country's

hottest drilling region, the Permian basin in West Texas and New

Mexico. After leading Texas last year, loan growth in the region

shrunk to 4.8% below the state's 7.5% average in the last quarter,

the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas said Thursday.

More than a decade into the shale boom, investors are trying to

wrap their arms around the true value of producers' assets, said

Michelle Foss, an energy fellow at Rice University's Baker

Institute. for Public Policy.

"There is a struggle now for investors to determine what things

are actually worth," Ms. Foss said.

Dwindling access to bank loans will put more pressure on an

industry that has already lost access to other sources of money.

Without new cash infusions, many companies may be unable to drill

their undeveloped reserves, which could further diminish the value

of their assets.

Some shale companies have been lobbying the Securities and

Exchange Commission to change its rules governing reserves

reporting, allowing them to count undeveloped assets as reserves

for a longer period. The SEC currently allows oil and gas producers

to report reserves as "proved" if the companies plan to develop

them within five years.

In an August letter to the SEC, Continental Resources Inc., one

of the largest shale companies, pushed for the regulator to extend

that period to 10 years. The company, founded by the billionaire

prospector Harold Hamm, said its proved reserves would be around

16% higher with such a rule change.

A Continental spokeswoman declined to comment. An SEC spokesman

didn't respond to a request for comment.

Write to Christopher M. Matthews at

christopher.matthews@wsj.com, Bradley Olson at

Bradley.Olson@wsj.com and Allison Prang at

allison.prang@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 22, 2019 05:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

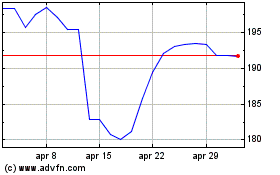

Grafico Azioni JP Morgan Chase (NYSE:JPM)

Storico

Da Mar 2024 a Apr 2024

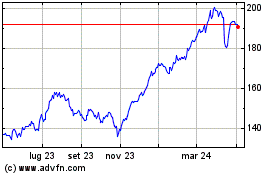

Grafico Azioni JP Morgan Chase (NYSE:JPM)

Storico

Da Apr 2023 a Apr 2024