Clash of agribusiness rivals will determine who dominates

farmland

By Jacob Bunge

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (January 7, 2020).

DECATUR, Ill. -- Before it was targeted by tens of thousands of

plaintiffs in lawsuits, Roundup was the king of the field -- the

world's most heavily used weedkiller. Now it's mired in court over

claims it caused cancer and viewed as a major liability for its

parent company, Bayer AG. On top of that, some weeds have evolved

to survive Roundup.

That has left an opening for a new contender to cover for

Roundup's failings, kicking off a clash of agribusiness rivals as

fierce as Pepsi's showdown with Coca-Cola on store shelves.

At stake are billions of dollars in herbicide and seed sales,

and influence over how farmers manage crops for decades.

Bayer, the German inventor of Aspirin, was already a leading

supplier of pesticides when it took control of Roundup as part of

its acquisition of Monsanto Co. in 2018. The merged company is the

largest seller of seeds and crop chemicals.

Bayer's big rival, seed and pesticide maker Corteva Inc., is

making moves to woo farmers away from the giant. On a sticky August

morning, Corteva field specialist Dan Puck stood before dozens of

farmers in an air-conditioned tent with screens flashing a green

thumbs-up logo of a new weed spray named Enlist.

Corteva erected the tent to help promote the weedkiller at the

late-summer Farm Progress Show. Following a magician performing

Enlist-theme tricks, farmers recounted losing battles against

Roundup-tolerant weeds like marestail, waterhemp and palmer

amaranth.

The Enlist spray, Mr. Puck told them, was a watershed in their

war on Roundup-resistant weeds. "People want a weed-control system

they have confidence in," he said. "We're filling a void right

now."

Roundup revolutionized farming when, combined with seeds

genetically engineered to tolerate the spray, it vastly simplified

weed control and helped farmers expand.

It is still No. 1, by most estimates. Many in the industry

expect it to stay there for the time being, because it still kills

a wider range of weeds than most other herbicides. It is used on

65% of major U.S. crops and is the biggest global herbicide brand,

according to research firm Phillips McDougall.

Roundup's dominance is waning, though, as U.S. farmers are

forced to supplement Roundup with other herbicides to dispatch

evolved weeds. That's where Corteva is taking on Bayer.

Corteva, formed following Dow Chemical Co.'s 2017 merger with

DuPont Co., is striking while its chief rival is vulnerable.

Bayer's weedkiller business, with 2018 sales of $5 billion, is

contesting lawsuits claiming Roundup causes cancer. Bayer argues

scientific studies prove Roundup's safety, a position backed by

regulators such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Though

some farmers have filed cancer lawsuits against Bayer, most remain

confident in the spray's safety and continue to use it.

Corteva aims to exploit another concern around its rival:

Bayer's new herbicide for Roundup-resistant weeds, XtendiMax, has

drawn complaints for damaging neighboring crops because its active

ingredient is susceptible to evaporating off plants, drifting on

wind and shriveling other crops. Bayer says its formulation of the

herbicide is less prone to drifting than older versions and that

complaints have declined as the company has trained farmers to

spray safely.

Corteva is dispatching representatives like Mr. Puck -- along

with a network of seed sellers, agronomists and others -- to sow

doubt about Bayer's newer spray among farmers and agricultural

retailers and win them over to Corteva's weedkiller.

The battle is on two fronts: weedkillers and seeds. For seed

suppliers, it is a chance to loosen Bayer's grip on lucrative

crop-gene licensing. Seed developers insert genes that let crops

resist specific herbicides -- creating, for example "Roundup Ready"

seeds -- and other seed companies must pay to license the genes

that provide that resistance. An estimated 85% to 90% of soybean

seeds sold in the U.S. contain Bayer's Roundup-tolerant genes,

agricultural-industry officials estimate. Rivals including Corteva

pay Bayer hundreds of millions of dollars a year to license those

genes for their own seeds, analysts estimate.

For consumers, the weedkiller war has implications because

herbicide-resistant weeds require farmers to spend more to keep

fields clean, adding expenses that can push up food costs.

Hard-to-kill weeds also threaten parks and wilderness areas.

Corteva and Bayer are pitching families of products --

weedkillers, along with the seeds and genetics that survive them --

under the brand names Enlist and Xtend, which includes the

XtendiMax spray. About 50 million U.S. acres last year were planted

with Bayer-developed soybean seeds resistant to XtendiMax, the

company estimated -- about 65% of U.S. soybean acreage. Corteva

sold a relatively small quantity of Enlist-resistant soybeans after

receiving regulatory approvals earlier last year.

By next summer, predicted Corteva Chief Executive James Collins,

one in 10 U.S. soybean fields will be planted with varieties

tolerant of its Enlist weedkiller. "Nothing would make me happier

than to be aggressive, " he said.

Brett Begemann, chief operating officer for Bayer's agricultural

business, said farmers and crop sprayers are getting better at

keeping XtendiMax under control and that Bayer's seeds produce

superior soybeans. "We're never afraid of competition," he said,

"or farmers having a choice."

The World Health Organization's International Agency for

Research on Cancer, which classified Roundup's active ingredient as

a probable carcinogen in 2015 -- Bayer has contested the

classification -- doesn't see the same risk in the new weedkillers.

In 2015, it classified so-called 2,4-D, Enlist's active ingredient,

as "possibly carcinogenic to humans," one step below the risk it

assigned to Roundup's active ingredient, glyphosate. The EPA says

2,4-D has low toxicity for humans and isn't a cancer risk.

The WHO agency hasn't evaluated the cancer potential of

XtendiMax's active ingredient, dicamba. While some studies have

linked dicamba exposure to non-Hodgkin lymphoma and birth defects,

the EPA doesn't consider dicamba likely to cause cancer in humans

and hasn't found evidence of chronic health problems from its

use.

Roundup's reign

Roundup is ubiquitous thanks to its ability to wipe out dozens

of weed species and to the debut of crops genetically engineered to

survive the weedkiller. Inserting those genes into corn, soybean,

cotton and other crops allowed companies to breed Roundup Ready

plants that could survive being sprayed with Roundup while plants

around them died.

Corteva's top seed brand, Pioneer, helped spread Roundup Ready

crops after it gave the new technology a stamp of approval among

farmers in the 1990s by licensing biotech genes from Monsanto. The

relationship soured as both companies expanded and launched

competing technologies, even as licensing deals kept them mutually

reliant.

On U.S. soybean fields, Roundup and other glyphosate-based

weedkillers rose from 15% of farmers' herbicide use in 1996 to 89%

in 2006, according to U.S. Agriculture Department data. By then,

about two-thirds of soybean fields were being sprayed solely with

glyphosate-based herbicides.

Roundup's power faded as weeds evolved. By 2002,

Roundup-resistant weeds were identified in Missouri, Tennessee and

some other states, according to the International Survey of

Herbicide Resistant Weeds. Six years later, resistant weeds were

popping up across the Midwest. In 2020, about 70% of U.S. soybean

fields will harbor Roundup-resistant weeds, estimates pesticide and

seed maker Syngenta AG.

Farmer Lynnet Talcott for years has fought Roundup-resistant

marestail and waterhemp weeds in her family's eastern Nebraska

fields. Extra herbicides required to kill them increased expenses,

but she was afraid to try Bayer's XtendiMax or other dicamba-based

weedkillers after nearby spraying damaged her soybeans, she

said.

"Your liability you're looking at is a major issue," she told

attendees in the Corteva tent at the Farm Progress Show, where she

joined other farmers on a panel discussing Enlist. Corteva covered

her travel and lodging for the event.

She and the other farmers described how the Corteva spray killed

weeds but didn't harm nearby crops and wildflower patches. "Peace

of mind," Corteva's Mr. Puck told the audience. "Such an important

benefit."

Studies and field work by university agricultural researchers in

Arkansas, Missouri, Tennessee and North Dakota have found 2,4-D,

the ingredient in Corteva's Enlist, to be less prone to evaporation

than dicamba, the ingredient in Bayer's XtendiMax.

Bayer has said its XtendiMax version of the herbicide holds

closer to where it is applied, that most crop damage has arisen

from farmers not following spraying instructions and that XtendiMax

doesn't drift when applied in the right conditions and with the

correct equipment. Ty Witten, Bayer's director of North American

crop-protection strategy, said complaints last year declined even

as XtendiMax-tolerant soybean acres expanded, showing farmers were

improving their control of the herbicide.

Weedkiller fistfight

Bayer's herbicide has divided farmers in some farm states since

it began selling the Xtend herbicide-and-biotech-seed combination

in 2017. There have been fistfights and even a murder over alleged

crop damage, according to Arkansas law-enforcement officials and

farmers. State and federal regulators have placed restrictions on

how it can be sprayed.

Farmers fear weeds more, and dicamba has proven effective

against weeds that can spread rapidly and choke out crops. Bayer's

biotech soybeans secured final regulatory approvals in 2016,

getting a jump that enabled the new seeds to capture a majority of

U.S. soybean fields.

Corteva's rival soybean products were held up for years by a

regulatory review in China, the biggest soybean importer, over

whether to approve their importation. China granted approval in

January 2019, and Corteva is racing to catch up, growing more

Enlist soybeans in its seed-production fields in Argentina, Brazil

and Chile.

To match Bayer's success, Corteva aims to also license out its

Enlist-tolerant crop genes to other seed companies, which pay fees

to insert those genes into their own soybean varieties. Corteva

estimates 120 seed companies, including Syngenta, have licensed

Enlist genes. Corteva could benefit from farmers needing to spray

those crops with Corteva's related weedkiller. Syngenta also

licenses Bayer's Xtend genes.

That means persuading local farm suppliers like Nathaniel Muzzy,

a Thief River Falls, Minn., seed and pesticide dealer who last year

began offering Corteva's Enlist products alongside Bayer's Xtend

line. He said Roundup-resistant kochia and ragweed arrived in

northern Minnesota around four years ago.

Bayer's XtendiMax works, he said, but farmers worry about

damaging neighboring fields, and local sales have been slow.

Farmers, he said, have been desperate for a solution.

When Corteva announced on Jan. 17, 2019, its planned launch of

Enlist-tolerant soybeans, Mr. Muzzy said farmers began asking him

about the products. He quickly switched about 40% of his

soybean-seed orders to Corteva's products and soon sold out.

"People don't want to spray and go to bed," he said, "and hope it

doesn't move and two weeks later, their neighbor's crop is

fried."

Bayer over the past two years has hosted XtendiMax training

sessions for farmers and crop sprayers across the Midwest to reduce

damaged fields and mitigate complaints. It said it has given away

over one million specialized nozzles that can produce herbicide

droplets that better stick to plants.

Last year, the 19 biggest soybean-producing states recorded

1,544 dicamba-damage complaints, versus 1,604 in 2018, according to

state agriculture officials. In 2016, the number was 257. Bayer is

developing a new XtendiMax version it says will better remain where

sprayed.

Defensive planting

Terry Fuller, who sells Bayer and Corteva products in Poplar

Grove, Ark., said farmers are interested in Corteva's spray. But,

he said, dicamba's proven weedkilling ability means many Arkansas

farmers will keep planting Bayer's XtendiMax-tolerant soybeans.

Some, he said, will plant them to ensure their crops aren't damaged

by an XtendiMax-using neighbor.

"I had a friend tell me," he said, " 'You either plant Xtend or

hate your neighbor.' "

Corteva is also a big customer of its big rival -- and would

like to change that. DuPont, Corteva's predecessor, in the

mid-2000s developed soybeans to resist Roundup and another

herbicide as a solution to Roundup-tolerant weeds. Monsanto sued

DuPont in 2009, saying DuPont's seeds illegally incorporated

Monsanto-patented genes. DuPont filed a countersuit accusing

Monsanto of unfair business practices.

They called a truce in 2013 after Monsanto prevailed in court.

DuPont agreed to a 10-year, $1.75 billion licensing deal to use

Monsanto-developed crop genes. That deal made Corteva a major

licenser of Bayer's XtendiMax-resistant soybean genes. About 65% of

Corteva's Pioneer soybean seeds use XtendiMax-tolerant genes,

Corteva officials said.

By early 2020, Corteva's Mr. Collins said, Corteva will know how

fast it can increase sales of its Enlist herbicide and seeds -- and

when it might scale back business with Bayer. "We write some big

royalty checks, " he said, "and would love to back ourselves out of

those as fast as we can."

One August afternoon, Corteva salesman Casey Mattke courted

farmers and agricultural retailers in a field near Whitewater, Wis.

In muddy boots, he led them past soybeans sprayed the previous week

with Enlist and then past rows of green pumpkin vines -- sensitive

to herbicides -- undamaged nearby. It is a presentation he and

colleagues gave over the summer at demonstration fields across the

Midwest.

Mr. Mattke pointed to a field across the road. "What if this was

an Xtend field?" he asked. Between the afternoon's moderate wind

and the government-mandated buffer to protect neighboring fields,

he said, spraying the Bayer product would be prohibited.

With Corteva's weedkiller, he said, "you could spray today."

Write to Jacob Bunge at jacob.bunge@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 07, 2020 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

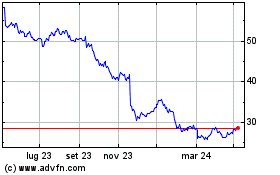

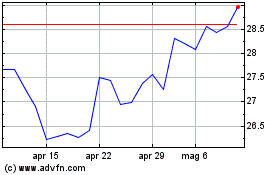

Grafico Azioni Bayer (TG:BAYN)

Storico

Da Mar 2024 a Apr 2024

Grafico Azioni Bayer (TG:BAYN)

Storico

Da Apr 2023 a Apr 2024