By Ruth Bender

In April last year, Bayer AG Chief Executive Werner Baumann was

on defense. The architect of one of the most disastrous

acquisitions in German corporate history, he had become the

country's first chief executive to lose a vote of confidence by

shareholders.

Almost a year later, with the German chemicals and

pharmaceuticals company closer to settling more than 42,000

lawsuits inherited from its acquisition of U.S. agriculture giant

Monsanto Co., and with a group-wide restructuring under way,

investors say Mr. Baumann might just manage to fix the mess he

made.

Bayer and plaintiff lawyers are approaching a deal in which

Bayer would pay a total of roughly $10 billion for current and

future plaintiffs who allege the company's Roundup herbicide causes

cancer, according to people familiar with the negotiations. Many

analysts say a settlement in that range would be positive for

Bayer.

Bayer declined to comment on the amount or time frame for a

settlement. The company argues that Roundup is safe when used as

instructed and has appealed the first three verdicts.

Expectations that the company could soon find a reasonable way

out of its legal morass have helped pull Bayer's shares up roughly

50% since they hit a seven-year low of roughly EUR52 last June.

But even Mr. Baumann's supporters say his window for fixing

Bayer might not stay open much longer. On April 28, the company

holds its next regularly scheduled shareholder meeting and many

investors expect Bayer to share at least a partial solution or

progress on how to resolve the legal battle before then.

Absent any progress, Mr. Baumann could face another

no-confidence vote, with another no being harder to survive,

investors say.

Mr. Baumann's $63 billion Monsanto acquisition in June 2018,

which he had been working on since well before becoming CEO that

same year, backfired after Bayer lost the first Roundup cases

before California juries, raising alarm in the market about

liabilities the company could face. Last spring, with Bayer's

market capitalization down more than a third since the first trial

loss, investors rejected a vote of confidence in the executive

board, a postwar first for a Dax-listed company.

Strong support from the company's nonexecutive directors helped

Mr. Baumann survive the vote. But investors also say he heard their

message.

The company last June boosted oversight of its legal defense,

including by creating a special board committee to monitor Roundup

lawsuits and naming a lawyer with expertise in mass torts to advise

the board. In October, it added an agriculture expert to its board.

All those measures were demanded by investors, including activist

investor Elliott Management Corp.

Another U-turn was Mr. Baumann's agreement to engage in

settlement talks with Roundup plaintiffs after he had previously

insisted that Bayer was willing to fight a yearslong court

battle.

Ingo Speich, head of sustainability and corporate governance at

Bayer investor Deka Investment, said the CEO also addressed

operational concerns by selling Bayer's animal health unit and

consumer-care brands on time and at good prices.

"Is he responsible for the legal issues? Yes. But he also showed

that he can keep the business together," said Mr. Speich, nine

months after blaming Mr. Baumann for "infecting a healthy Bayer

with the Monsanto virus."

Within Bayer, employees say, Mr. Baumann has also worked to

restore confidence and team spirit following what some describe as

a meltdown in morale a year ago. Last spring, he held video town

halls to reassure staff each time the company faced a new legal

setback in the U.S., according to one midlevel executive.

"Last year people talked about the lawsuits all the time, now

it's mostly business as usual," the person said. A lull in trials

has helped, according to people familiar with the company: Bayer

and plaintiff lawyers have agreed to postpone dozens of cases since

they started settlement talks last fall.

Among the company's many deeply anchored traditions is its

ownership of Bundesliga soccer club Bayer 04 Leverkusen, whose home

matches are must-attend occasions for top executives. At a recent

soccer match with fellow senior managers, Mr. Baumann seemed

optimistic about the future of the company and how it is growing,

according to a person present at the meeting.

"There is a feeling there is light at the end of the tunnel,"

the person said.

Mr. Baumann, the son of a baker, spent over 30 years working his

way up from Bayer's finance department to CEO. People who know him

say he is cerebral, detail-oriented and rational. The CEO often

brings a small notebook to meetings where he writes down questions

he needs to follow up on, according to people who have worked with

him. Others say he can summon minute details, such as the number of

participants in a continuing clinical drugs trial, off the top of

his head.

With the exception of Mr. Baumann's predecessor, the

Dutch-American Marijn Dekkers, Bayer CEOs have always been Bayer

lifers. Many, like Mr.Baumann and current Chairman Werner Wenning,

even hail from the Rhineland region, where Bayer is based.

Several of the group's top leaders, Messrs. Baumann and Wenning

included, lived through a similar crisis at Bayer in the early

2000s, when the company faced thousands of U.S. lawsuits over its

cholesterol-lowering drug Baycol. Bayer had to pull the drug after

it was linked to serious injuries and even death, and the company's

share price fell to an all-time low of EUR10.

During his time as CEO, Mr. Wenning improved Bayer's position by

spinning off assets, cutting jobs and eventually settling the

claims for much less than investors had feared.

When Bayer set out to grow again, Mr. Baumann, described by many

as Mr. Wenning's protégé, proved himself a talented number cruncher

during the integration of German pharmaceuticals company Schering

AG, according to people present at the time.

The fact that Mr. Wenning did pull Bayer out of trouble made him

something of a legend within the company. People familiar with

Bayer said Mr. Baumann would need to deliver much more than a

settlement to achieve a similar status.

Besides striking a settlement at the low end of expectations,

investors say the CEO still needs to demonstrate how Monsanto will

make Bayer thrive.

The lawsuits aside, Roundup is facing competition from a

determined rival. Seed and pesticide maker Corteva Inc., is making

moves to woo farmers away from Bayer products.

For Deka's Mr. Speich, a full judgment on the Monsanto purchase

-- and thus on Mr. Baumann -- will only be possible some two years

from now, once the agriculture business is fully integrated.

Mr. Baumann has said repeatedly that buying Monsanto was the

right move, saying it will position Bayer as leader in a market

with enormous growth potential given the world's fast-growing

population.

Meanwhile, once the legal fight is resolved, some analysts say

investors could push Bayer to consider the merits of splitting its

pharmaceuticals and crop-science businesses. People familiar with

Bayer's thinking said the company would likely fight any push for a

split, arguing that its existing plan to boost sales and profit

through 2022 will create more value for shareholders.

"A settlement would of course be positive but I think it will

grant Mr. Baumann only a short respite," said Markus Mayer, analyst

from Baader Bank.

-- Ben Dummett in London, Laura Kusisto in New York and Jacob

Bunge in Chicago contributed to this article.

Write to Ruth Bender at Ruth.Bender@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 10, 2020 06:18 ET (11:18 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

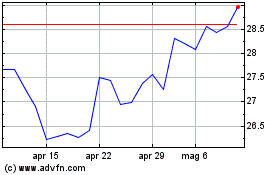

Grafico Azioni Bayer (TG:BAYN)

Storico

Da Mar 2024 a Apr 2024

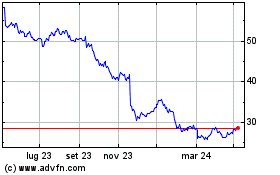

Grafico Azioni Bayer (TG:BAYN)

Storico

Da Apr 2023 a Apr 2024