By Laura Kusisto, Ruth Bender and Jacob Bunge

Bayer AG faces an extraordinary challenge as it tries to settle

tens of thousands of claims that its Roundup weedkiller causes

cancer: The product remains on the shelves, making it almost

impossible to put the litigation to rest forever.

Experts say Bayer is in an unusual position compared with other

companies that have faced multibillion-dollar lawsuits over their

products. To end mass-tort litigation, other companies generally

have discontinued or altered their products or added warning labels

-- all of which are problematic for the German pharmaceutical and

agricultural firm.

"If you're still putting out a product that people claim injures

them, I don't know how they can insulate themselves from future

liability," said Carl Tobias, a University of Richmond law

professor who studies product-liability cases. "I think they're in

a bind."

Bayer is moving closer to a settlement potentially totalling $10

billion, people familiar with the matter said, making it one of the

most complex and costly corporate litigation cases ever. Many

investors are demanding clarity and expect Bayer to deliver at

least a partial solution before the company's next annual

shareholder meeting in late April.

But Bayer's case is tricky because regulators including the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency have said that glyphosate, the main

chemical ingredient in Roundup, doesn't cause cancer. The agency

said last year that manufacturers like Bayer can't put cancer

warnings on glyphosate-based herbicides like Roundup, and that

states can't require such labels. The company also can't alter the

product to remove glyphosate -- which plaintiffs claim poses a

cancer risk -- because it is the herbicide's main weedkilling

chemical.

Bayer has said repeatedly that glyphosate will remain an

important product and has applied for re-approval of the chemical

in the European Union, where some countries including Germany are

banning sales.

Bayer Chief Executive Werner Baumann has said any settlement

framework must come "relatively close" to guaranteeing Bayer won't

face a future wave of lawsuits. People familiar with Bayer

management's thinking said the company would take its time to reach

such a settlement, even if it angers investors seeking clarity

before the annual meeting.

The settlement talks come after Bayer lost its first three

trials with juries awarding some $2.4 billion to plaintiffs --

later reduced by judges to about $190.5 million. Bayer has

appealed, but those processes could take years to play out.

"The trials have gone so spectacularly bad for Bayer that they

don't want to go in front of another jury," said Adam Zimmerman, a

law professor at Loyola Law School, Los Angeles.

Experts said they couldn't identify another company that has

settled yet persisted in selling a product unaltered and without a

warning label. Johnson & Johnson has continued selling its

talcum powders while defending itself against some 17,000 lawsuits

alleging they cause ovarian cancer or mesothelioma, and that

J&J failed to properly warn consumers of this purported risk.

The company will face similar questions if it decides to settle the

cases.

Roundup remains on many hardware store shelves, creating a vast

pool of home gardeners who could claim it caused their cancer.

Pulling Roundup from the consumer market would cost Bayer about

$200 million in annual sales, Bernstein analysts have

estimated.

Roundup accounts for around 5% of Bayer's total sales, the

company has estimated -- sold mostly to farmers, who have stuck by

Roundup despite the cancer litigation.

The Roundup dilemma led investors last year to reject a

confidence vote in Mr. Baumann, whom some blamed for the legal

problems that followed Bayer's $63 billion acquisition of biotech

seed giant Monsanto Co. in June 2018. Monsanto is the maker of

Roundup.

Bayer lost about a third of its market value as the first jury

verdicts rolled in. The shares have bounced back since the company

and plaintiffs' attorneys began settlement talks last summer and

have agreed along the way to postpone trials. If talks were to

collapse and trials resume, Bayer's share price could get stuck in

another rout, analysts say.

Of the $10 billion under consideration in settlement talks, $8

billion would be used to pay current plaintiffs and $2 billion

would be set aside as a fund for future claims, according to people

familiar with the matter. That would exceed recent big-ticket

payouts such as Merck & Co. Inc.'s nearly $5 billion settlement

over its painkiller Vioxx and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.'s

roughly $2.4 billion settlement over allegations its diabetes drug

caused bladder cancer.

Many analysts say a settlement in that range would still be a

positive outcome for Bayer. But even then, it is difficult to

guarantee such a figure wouldn't eventually surpass $10 billion,

academics and lawyers say. They said the settlement under

discussion couldn't bar future plaintiffs from attempting to sue if

they deem the payouts from the $2 billion fund insufficient or if

it runs out, potentially exposing Bayer to future liability.

Even if it decided to stop selling Roundup, partially or

entirely, plaintiffs could theoretically still sue a few years from

now, experts say. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the type of cancer

plaintiffs say glyphosate causes, can take years to develop.

Experts said certain measures could help discourage future

litigants. As part of the settlement, plaintiff attorneys could

agree not to advertise and recruit future litigants. The federal

judge overseeing the settlement could order that any future

litigants each produce their own expert report linking their cancer

to Roundup when filing a case. That would be a hurdle for attorneys

who file large numbers of cases at once, costing several thousand

dollars per expert report.

Bayer could also eventually win its appeals, giving it an upper

hand that would discourage future plaintiffs from suing -- or even

wipe out remaining lawsuits, if a higher court rules that the

company can't warn about a cancer risk that regulators have

determined doesn't exist.

"There is a way to get more peace," Mr. Zimmerman said. "I just

don't know if it will be global peace."

Write to Laura Kusisto at laura.kusisto@wsj.com, Ruth Bender at

Ruth.Bender@wsj.com and Jacob Bunge at jacob.bunge@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 12, 2020 14:45 ET (19:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

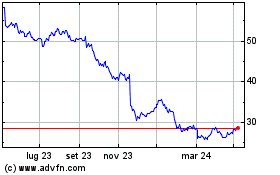

Grafico Azioni Bayer (TG:BAYN)

Storico

Da Mar 2024 a Apr 2024

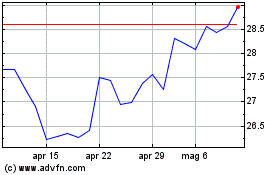

Grafico Azioni Bayer (TG:BAYN)

Storico

Da Apr 2023 a Apr 2024