By Brent Kendall and Asa Fitch

SAN FRANCISCO -- A federal appeals court appeared receptive to

Qualcomm Inc.'s appeal of a ruling that found it was illegally

maintaining a monopoly in cellphone chips and extracting

unreasonably high royalty rates for patents that are essential to

the industry.

A three-judge panel of the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals

repeatedly questioned arguments by the Federal Trade Commission,

which sued Qualcomm in 2017 for alleged antitrust violations.

Near the end of the hourlong hearing Thursday, Judge Consuelo

Callahan suggested Qualcomm's practices had been "overly

capitalistic but not necessarily anticompetitive." She also voiced

skepticism of FTC arguments that Qualcomm's tactics had unlawfully

raised costs incurred by its chip rivals.

Judges on the panel said that, even if the evidence showed that

Qualcomm charged high royalty rates for its patents, that wasn't

necessarily evidence that the company had stifled the competitive

process.

"Anticompetitive behavior is illegal under the Sherman Act.

Hypercompetitive behavior is not," said Judge Stephen J. Murphy, a

visiting judge from Michigan. "This case asks us to draw the line

between the two."

The case cuts to the heart of Qualcomm's business model and

promises broad stakes for two areas of the law that are often in

tension -- antitrust, which is designed to promote competition, and

patent law, which gives intellectual-property owners the right to

exclude competitors from using their inventions unless they pay

licensing fees.

The litigation also comes with an unusual twist: Two different

government agencies that enforce U.S. antitrust laws disagree on

whether Qualcomm's conduct is unlawful and argued against one

another Thursday.

San Diego-based Qualcomm designs and markets chips that

facilitate cellphones' communications with cell towers. It owned

about 43% of the global market for such chips, according to a

Strategy Analytics report from last year's second quarter.

The company also has a licensing arm that collects royalties

when others use a portfolio of more than 140,000 patents

world-wide, many of which cover key telecommunications

technologies. Licensing revenues are only a fraction of chip sales,

but the division is a driver of Qualcomm's overall profits because

its margins are much better.

The Federal Trade Commission sued Qualcomm in the final days of

Democratic control under the Obama administration. It focused on a

central Qualcomm business policy that FTC lawyers described as "no

license, no chips."

The FTC said Qualcomm enjoyed monopolies in two types of modem

chips and wouldn't sell those must-have chips to device makers

unless those companies also paid to license a broader portfolio of

Qualcomm's patents. That structure made it difficult for phone

makers to challenge Qualcomm's royalty rates, and the arrangement

also meant those manufacturers were paying Qualcomm royalties even

if they used a competitor's chips in their phones, FTC lawyer Brian

Fletcher told the panel.

Judges indicated they weren't convinced.

"Is that the standard, making it more difficult for

competitors?" asked Judge Johnnie Rawlinson. "Because that's the

nature of business, to make it more difficult for your competitors

to operate."

"If you're making it hard for competitors because you have a

better product or you sell it for less, no problem," Mr. Fletcher

responded. "That's not this case."

Apple Inc. sued on similar grounds, but the iPhone maker and

Qualcomm settled their differences in April last year, dropping all

litigation and reaching a new chip-supply agreement.

U.S. District Judge Lucy Koh in San Jose, Calif., ruled against

Qualcomm last May. She agreed the chip designer improperly

leveraged its market dominance and ordered Qualcomm to change the

way it does business. If her ruling holds, Qualcomm would be forced

to renegotiate existing patent licenses without taking into account

chip-supply deals, which could dramatically lower licensing

revenues.

Even before Thursday's hearing, the Ninth Circuit already had

stayed the effect of that ruling for now.

The court, both in its stay order and during the hearing,

suggested Judge Koh was on shaky ground in at least part of her

ruling, when she found that Qualcomm had obligations to license

certain industry-essential patents to rivals.

Qualcomm says it acquired its market position through ingenuity

and business acumen, and argues that its licensing practices make

sense because every cellphone invariably uses its patented

technologies.

Qualcomm's lawyer, Thomas Goldstein, said the company invested

$60 billion in a vibrant industry, on the prospect that it would be

able to collect royalties and realize financial success.

Mr. Goldstein didn't dispute that the company had monopoly power

in communications chips, but argued it hadn't used that power to

freeze out competitors. "What has gone wrong in the competitive

process? The answer to that question is nothing," he said.

The company has gained a powerful ally in the past year: the

Justice Department, which argued in defense of Qualcomm at

Thursday's hearing.

The department has said Judge Koh made fundamental errors and

imposed harsh penalties that could hurt innovation and impair a

company that is critical to maintaining the U.S.'s technology

advantage over global rivals.

Qualcomm is a leading U.S. purveyor of superfast

fifth-generation cellular technology, and the U.S. sees the

company's health as crucial to maintaining a 5G advantage over

China, which is rapidly deploying the networks.

A decision is expected in the coming months.

Write to Brent Kendall at brent.kendall@wsj.com and Asa Fitch at

asa.fitch@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 13, 2020 16:45 ET (21:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

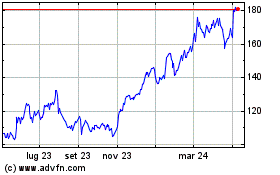

Grafico Azioni QUALCOMM (NASDAQ:QCOM)

Storico

Da Mar 2024 a Apr 2024

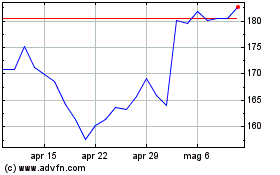

Grafico Azioni QUALCOMM (NASDAQ:QCOM)

Storico

Da Apr 2023 a Apr 2024