By Laura Kusisto

The bail-bond industry is under intense pressure as more states

virtually wipe out cash bail and financial firms look for an exit

from an increasingly controversial profit center in the

criminal-justice system.

Most recently, private-equity firm Endeavour Capital says it has

sold its stake in California-based Aladdin Bail Bonds, one of the

country's largest bail bond providers. The move came after

Endeavour and its investors faced pressure from the American Civil

Liberties Union and others who say bail is part of a justice system

that discriminates against minorities and low-income

defendants.

Endeavour follows other major financial firms that have

abandoned the bail bond industry, amid falling revenues, growing

criticism from activists and an uncertain political environment.

Tokio Marine HHC, a Houston-based insurance company owned by

Japan's Tokio Marine Holdings Inc., said in April it was selling

Bail USA Inc., a bail-bond underwriter, and no longer providing

insurance for bail bond companies. Randall & Quilter Investment

Holdings Ltd., an insurance company based in Bermuda, said in a

December 2018 financial report that it was divesting itself of its

U.S. bail bond business.

Endeavour didn't respond to questions about why it sold Aladdin,

and hasn't disclosed the buyer in the recent sale.

Aladdin and Randall & Quilter didn't respond to requests for

comment.

The decisions to exit bail-bond companies come as the industry

enters a period of decline. The amount of bail bonds written has

fallen about 10% to just over $14 million in 2018, according to an

analysis of industry data by insurance-ratings firm A.M. Best Co.

From 2009 through 2016 the industry grew by about 25%, but more

recently it experienced two straight years of declines.

Bail-bond companies have long been essential to the U.S.

criminal-justice system, helping defendants who can't afford bail

get out of jail by posting the cash for their release and ensuring

they show up in court. In exchange, they charge a fee of about 10%

of the amount of bail and can seize collateral if a defendant

misses court.

The most serious pressure on the bail-bond industry has been a

host of changes to local laws governing how judges release inmates

pretrial, as state politicians question the value of bail. More

than 20 states and numerous counties have largely eliminated cash

bail for low level and nonviolent offenders in recent years.

"If criminal-justice reform were to take effect in enough

states, they could be in serious trouble," said David Blades, a

senior industry analyst at A.M. Best, of bail-bond companies. He

added that he doesn't believe the industry is yet under existential

threat.

Industry experts said the bail industry's gradual decline could

become a free fall if a law passed in 2018 goes into effect in

California. The state is by far the industry's largest market,

accounting for one-quarter of the bail-bond industry's revenue,

according to the American Bail Coalition, a trade association for

bail insurance companies.

The California measure would replace cash bail with an algorithm

that would help determine whether those accused of a crime were

safe to be released. Implementation has been suspended until a

referendum is held in November.

"Everybody is collectively holding their breath to see what

happens in California," said Jeff Clayton, the American Bail

Coalition's executive director.

Even without specific regulatory changes, Mr. Clayton said the

industry is finding itself under pressure because judges are

letting more low-risk offenders go free, leaving bail-bond

companies to deal with higher-risk offenders who require more

monitoring.

Activists have also targeted the bail-bond industry by

pressuring insurers and financial firms that "provide the financial

underpinning for the entire bail bond industry," said Udi Ofer,

director of the justice division at the ACLU.

The ACLU and another progressive civil-rights advocacy group,

Color of Change, embarked on a campaign that included sending

letters to Endeavour and meeting with the private-equity firm to

try to get it to sell its stake in Aladdin, which the fund

described as the largest retail pretrial release service provider

in the country, operating 50 locations and employing 600

people.

When that failed, Mr. Ofer said, they targeted pension funds and

university endowments that invested in Endeavour's most recent

fund. Many of those groups were based in Endeavour's home state of

Oregon, which doesn't allow commercial bail bonding.

"We believe the bail industry would benefit from certain

reforms," John von Schlegell, managing director and co-founder of

Endeavour, wrote last year in a letter to a consultant who worked

on the ACLU's campaign. "We offered to discuss those and other

reform ideas with you and you disregarded that offer, stating your

overriding opposition to any private enterprise involved in the

criminal justice system."

Mr. Ofer called Endeavour's decision to sell Aladdin "a major

milestone in the movement to end the for-profit bail industry in

the United States and end the practice of wealth-based

incarceration."

An investor group led by Endeavour purchased a controlling stake

in the holding companies affiliated with Aladdin in 2012, according

to an annual financial statement from one of those companies,

Seaview Insurance Co.

Multiple Endeavour investors declined to discuss the firm's

decision to exit its Aladdin investment, saying that they didn't

have input into how the private-equity firm invests their

funds.

Ben Eisen contributed to this article.

Write to Laura Kusisto at laura.kusisto@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 21, 2020 10:50 ET (15:50 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

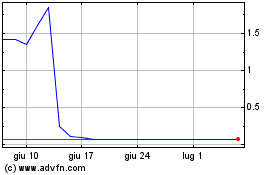

Grafico Azioni R&q Insurance (LSE:RQIH)

Storico

Da Mar 2024 a Apr 2024

Grafico Azioni R&q Insurance (LSE:RQIH)

Storico

Da Apr 2023 a Apr 2024