Appeals Court Rules In GSE Case But Not That GSE Case

19 Agosto 2016 - 4:30AM

Dow Jones News

A federal appeals court finally issued a decision in a

long-running dispute over actions taken by the U.S. government

after it put Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into conservatorship in

September 2008.

It wasn't, however, the decision that many investors,

housing-policy wonks and the government have been eagerly awaiting.

That decision, reviewing a federal judge's dismissal of a case

brought by Fannie and Freddie shareholders protesting the

government's claim on profits, will come out of the U.S. Court of

Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.

Thursday's decision came from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the

Federal Circuit, the other group of federal courts based in the

District of Columbia. It wasn't brought by shareholders protesting

the government's claim on Fannie's and Freddie's profits, it was

brought by the former chief financial officer of Freddie Mac.

Still, Investors Unite, a group that advocates for Fannie and

Freddie shareholders, described the decision as a "positive sign"

in a tweet.

That's half-right. There certainly are parts of the ruling that

may benefit shareholders. But there are other parts that may hurt

them.

The case decided Thursday was brought by Anthony Piszel, who was

named Freddie's CFO in 2006. His contract said that if he was fired

from the position without cause, he would get a severance package

that would include a lump-sum payment equal to twice his annual

salary and that his restricted stock units would continue to

vest.

Shortly after Freddie was seized by the government, Mr. Piszel

was fired at the behest of the director of the Federal Housing

Finance Agency, which had become Freddie's conservator. The

director also determined that Freddie shouldn't pay Mr. Piszel any

severance payment.

Mr. Piszel sued in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims six years

later, arguing that the cancellation of his severance payment was a

taking by the government. Under the Fifth Amendment's "takings

clause," the government must provide compensation when it deprives

someone of property.

Last summer, a federal judge dismissed Mr. Piszel's case. Citing

earlier cases in which federal courts held that shareholders of

failed banks lacked property interests that could give rise to a

takings claim, the judge ruled that Mr. Piszel's contract didn't

create a property right for which he could demand compensation.

The judge said by signing a contract with a company as

pervasively regulated as Freddie Mac, Mr. Piszel had assumed the

risk that future regulation might change or eliminate benefits or

compensation promised to him. That argument had been used to turn

away suits by bank shareholders after the lenders were seized by

the Federal Deposit Insurance Co.

Even though it ultimately agreed with the dismissal, the appeals

court disagreed with the argument. It said that Mr. Piszel's

contract did create a property right. The court pointed out that

the law that authorized the FHFA to bar a severance payment to Mr.

Piszel wasn't passed until the summer of 2008, after he had entered

into the contract with Freddie. This is the part that is good news

for Fannie and Freddie shareholders: Some of the lawsuits also make

claims based on the takings clause. After this ruling, it is more

likely that federal judges in those cases will hold that they also

have property rights arising from ownership of shares.

But they shouldn't get too giddy. Keep in mind that the appeals

court upheld the dismissal. It ruled that while Mr. Piszel's

contract really did create a property right, nothing the government

did took that right away from him.

That needs a bit more explanation. After all, the FHFA really

did tell Freddie to fire Mr. Piszel and not to pay any severance.

And Freddie did both those things. By Mr. Piszel's reckoning, the

severance package would have been valued at $7 million. How could

the government deny him that without taking anything from him?

The court ruled that the FHFA's instructions didn't take

anything from Mr. Piszel because he still had the right to enforce

his contract in a breach-of-contract lawsuit against Freddie Mac.

Although he wouldn't have been able to force Freddie to live up to

the contract, he could have sued for damages equal to the value of

the promised severance. And since he still had that right to sue

for breach of contract, he still had the property interest created

by the contract.

This is a particularly tough line of reasoning for Mr. Piszel

because the statute of limitations on breach-of-contract claims ran

out years ago. So the appeals court is telling him that he brought

the wrong kind of case to the wrong court at the wrong time.

It may also be bad news for shareholders, at least those hoping

for a win on the takings claims.

Many of the investor lawsuits also make breach-of-contract

claims. Holders of preferred shares of Fannie and Freddie argue

that the government's claim to all of the profits of the companies

denies them contractual rights to dividends and specified

liquidation preferences. Common shareholders also claim their

rights to dividends and to the residual value of the company has

been violated.

Under the logic of the appeals court in Mr. Piszel's case, if

shareholders have the right to sue for breach of contract, there

may not have been a taking at all. Sure, all the value of the

companies now accrues to the government but if shareholders can sue

for breach of contract, the government arguably hasn't taken

anything from them.This isn't necessarily awful news for

shareholders. It doesn't foreclose all chances of a legal victory,

but it may mean that their takings claims will get dismissed. That

is a setback because many of the investors believe that this was

their best line of legal argument.

Write to John Carney at john.carney@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 18, 2016 22:15 ET (02:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

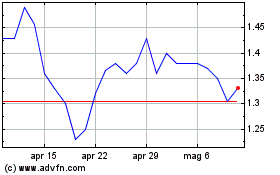

Grafico Azioni Federal Home Loan Mortgage (QB) (USOTC:FMCC)

Storico

Da Mar 2024 a Apr 2024

Grafico Azioni Federal Home Loan Mortgage (QB) (USOTC:FMCC)

Storico

Da Apr 2023 a Apr 2024